Italian film maker focuses on China's urban youth

|

|

|

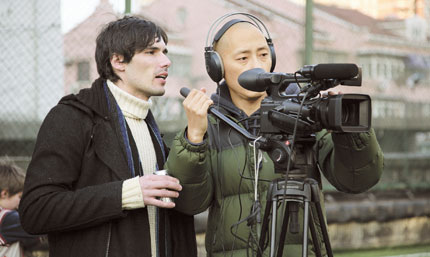

Italian film maker Gianpaolo Lupori and his crew shoot a commercial for a beer company in Harbin, Heilongjiang Province. |

The lives of young people in China's fast-changing urban environments fascinate Italian film maker Gianpaolo Lupori, who delves into Shanghai's metropolis to tell stories from the fringes of the mainstream.

In his film "Meatspace," recently screened at the Chong Qing Film Festival, Lupori looks at young Chinese who spend so much time online in cyberspace that they refer to their "real lives" as time spent in "Meatspace."

The inspiration for the 17-minute film came while Lupori was working in a computer games company in Shanghai.

The characters are "real people," not actors, and some were the online enthusiasts that Lupori worked with.

They talk in Shanghai dialect, with English and Mandarin Chinese subtitles.

"I researched online, but not understanding Chinese was a huge handicap. But through working with these kids, who also acted in the film, I was able to understand a lot more," he says.

"Meatspace" is very much about what is happening in China, he says.

Lupori, who has lived in Shanghai since 2004, says he was drawn to the idea of people who identify more with their online life than their day-to-day reality.

"Not knowing Chinese I had to take information second- or third-hand about the online world of these kids but I kind of like that," he says.

"Before I did the film, I hadn't played an online game, and as an outsider in the culture you have a unique position as an observer. You can see things that those who are totally involved in that life may not."

"Meatspace" was shot on just 1,200 yuan (US$176) and Lupori hopes it will become the pilot of a full-length feature film.

He worked extensively with the Shanghainese actors to make sure the dialogue was right and that it reflected the way a young online computer enthusiast would speak.

Lupori has shot another two short films, again on shoestring budgets of less than 1,500 yuan each.

One of the films, the 12-minute "Dark Moon" is about problems of making connections in a big city. It was screened at Shanghai's Meiwenti film festival in June 2008.

His third movie, still untitled, was filmed this year and follows the mishaps of a young man who finds a bag on the street of Shanghai and tries unsuccessfully to get rid of it.

Lupori would like to screen all the three films together because they are all urban stories about local people, "universal stories but very localized."

Telling stories from China's urban heart might seem a leap for Lupori, who grew up in the barren rural landscape of southeastern Italy in countryside near the port city of Bari.

At first he followed his parents, working in childhood education that runs arts, crafts, music and multimedia activities to engage children in learning.

He worked with underprivileged children and new immigrant families. He also taught English in Italy.

Lupori came to Shanghai because the parents of his wife, Nadya Alexander, were working in the city. The couple has two children, Shawn, 9, and Aidan, 8. Alexander teaches at a Montessori school.

"The plan was to stay six months or a year at most but we got caught up in the spirit of the potential that is such a part of Shanghai," Lupori says.

He taught English before moving into acting and film. On arriving he quickly gained a toehold in the local film community, getting parts as an extra in Hollywood films "The White Countess" and "The Painted Veil." He was also a stand-in for Jonathan Rhys Myers in "Mission Impossible 3."

He was a runner on sets, organizing actors and equipment on shoots. In 2007 he got a part in a high-profile commercial for electronics manufacturer Philips Global that was directed by acclaimed director Wong Kar-wai.

He also has been directing programs for Luxe, a series of in-flight television shows featuring China's luxury goods industry, for Shanghai Airlines.

Looking back on five years in Shanghai, Lupori says he has forged a career in the local film and media industry that would not have been possible in his home country.

"The media industry in Italy is very closed, and there is no room for innovation and it is all in the hands of a few people," he says.

"Film making is not what it used to be in Italy - I thought I might be able to be a critic or something but never what I have been able to do here."

0 Comments

0 Comments