Emperor's private collection gets public viewing in New York

Currently showing at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Emperor's Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City showcases about 90 works of art created for the emperor Qianlong (1736-95), a man whose desire to unify "all under heaven" is clearly noted in the extravagance of this loan exhibition organized by the Peabody Essex Museum.

|

|

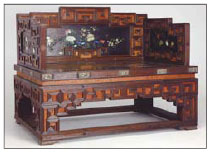

A throne displayed at The Emperor's Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City. [China Daily] |

"Drawn almost entirely from the miraculously preserved Qianlong garden, this exhibition provides a unique opportunity to experience the material richness and artistic diversity of the Qianlong era," says Maxwell Hearn, the Douglas Dillon Curator in the Department of Asian Art at the museum.

"The Metropolitan has important holdings of Qing court painting and decorative arts, but this is the first time these works could be set within the context of an integrated architectural environment."

Designed to fill a lush retirement retreat for the emperor built deep within the walls of the Forbidden City in 1771, the collection includes beautiful pieces that seem impressive even now.

A large-scale scroll mounted on imperial yellow features a portrait of the emperor, whose advancing age is visible in the bags under his eyes.

The portrait is done in the classical Chinese style, with the emperor facing forward in a regal manner. However, hints of Western influence are visible.

"The subtle use of light and shade to model his facial features as well as the folds of his robe reveal the influence of Western style pictorial techniques," reads a museum description of the piece.

Indeed, the emperor, who presided over China's last dynasty, the powerful Qing, seems particularly open-minded in retrospect.

Buddhist and Tibetan influences are also visible in pieces that feel distinctly different from those done in the classical Chinese style. One stunning three-dimensional panel features dozens of tiny alcoves, filled with clay figures of Buddhist deities and teachers.

"The Qianlong Emperor's interest in objects from different cultures seems to reflect his belief that his rule was recognized beyond the immediate borders of the Qing empire," Hearn says.

"His devotion to Tibetan Buddhism may also be understood as an affirmation of his status as a Buddhist 'Chakravartin' or 'universal ruler'. The Tibetan-style panel with niches presents the emperor as a manifestation of Manjusri (Wenshu Buddha), the Bodhisattva of Wisdom."

The emperor was a highly skilled calligrapher and though this seems unusual for such a powerful man, Qianlong was closely involved in curating his retirement garden, which strived to honor the artistry of a ruler who wrote more than 40,000 poems.

In one corner of the exhibition sits an enormous rootwood chair, which is the emperor's imitation of similar pieces used during ancient purification traditions. The rituals featured poetry-writing competitions fueled by wine, and were held on waterways, a feature the emperor attempted to replicate within the garden by building carved stone canals.

A few turns later, and visitors to the museum will find themselves in the building's own courtyard, built in traditional Chinese style. A manicured garden sits by a fountain, where on this particular winter day, a number of small children sat sketching the architecture. The exhibition implies that Qianlong would have wanted it just so.

The Emperor's Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City will remain on display through May 1, 2011.

0

0