Shipping industry woes

Hu Keyi is one of China's shipbuilders in the eye of the storm of the economic crisis.

The 47-year-old is chief engineer at Jiangnan Shipyard, one of China's oldest shipbuilders based in Shanghai.

The company, which employs 10,500, has seen its gross profits on its ships fall by 75 percent since the beginning of the economic crisis.

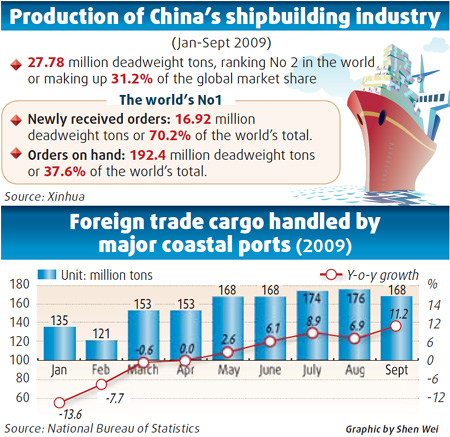

Jiangnan is far from alone. In the first nine months of this year, new orders received by China's shipbuilding yards were 16.9 million deadweight tons, a massive 70 percent drop from 57.2 million tons in the same period last year, according to the China Association of the National Shipbuilding Industry.

Hu said new orders from shipping lines from around the world have all but dried up.

"We almost don't have any orders from abroad at the moment. We still have orders coming in from domestic State-owned companies and also from some private companies. They are trying to grab good ships at historically low prices," he said.

China's shipbuilding industry has been hit hard by the slump in world trade. According to the World Trade Organization, international trade in and out of China fell by 20 percent in the first nine months of this year and by 17 percent across the globe.

According to the Chinese Ministry of Transport, container throughput into the country was down 7 percent from 126 million teus (container units) last year to 117 million teus this year.

A cold wind is also blowing across the 3 sq km shipyards at Liaoning Marine and Offshore Industrial Park on the western edges of Yingkou City in Liaoning province.

"China's shipbuilders need to hug to keep warm. We need to come together and cut costs so as to continue our operations," said Sun Jimin, the general manager of the company.

"Shipbuilders now have great capital problems. I hope the government can come up with a policy to promote buyers' credit so that they can make orders. I am waiting for a big order of four ships from Britain. It would be good if our government could lend money to our buyers," Sun said.

Slashing prices

Meanwhile, Liaoning is slashing the price of its ships by as much as 40 percent in a bid to find orders.

"We are reducing the price of ships sharply in a bid to find new buyers. Ships that might have cost $50 million are now being priced at $30 million, but still we don't have any orders right now," Sun said.

He said the current situation is in huge contrast with last year, when trade was booming.

"We were very busy then, but now it is very different. It is no longer a problem of how to make money but about how to reduce losses," Sun said.

Analysts estimate that the combined losses this year of shipping lines will be some $20 billion.

|

|

|

The newly built Jiangnan Shipyard on Shanghai's Changxing Island is ready for new business. "The shipyard is poised to accept the order of building China's first aircraft carrier, and with our own intellectual property rights," said Nan Daqing, general manager of Jiangnan Shipyard (Group) Co Ltd. [CFP] |

Losses in the first six months of this year already make depressing reading for the carriers. The Japanese shipping line NYK has reported a net loss of $694 million, the German Hapag-Lloyd line $680 million, China's State-owned giant Cosco $671 million and APM-Maersk of Denmark $706 million.

The number of ships laid up in locations around the world, including a whole ghost fleet off the coast of Singapore, is now attracting international attention.

As of October, it was estimated that some 10.7 percent of the world's container capacity is now laid up, a total of some 500 ships. Some in the industry have called for drastic emergency measures to breathe new life into the shipbuilding industry.

Gao Yanming, chairman of Hebei Ocean Shipping Co, based in Qinhuangdao in Hebei, said he believes the world's shipping industry is on a precipice.

Gao recently told the World Shipping Summit in Qingdao that the Baltic Dry Index (BDI), the measure that tracks world shipping prices and which has recently rallied to above 4,300, must not fall further.

"If the BDI falls below 3,000, the market will fall into hell, " he said.

And he called for all ships more than 23 years old to be scrapped in order to reduce capacity and give new life to shipbuilders.

Scrapping ships

"The more we scrap, the better the market will be," Gao said.

The major problem facing world shipbuilders is what to do with the capacity they have built up over recent years.

Global shipyard capacity is set to increase by 161 percent from 26 million compensated gross tons (cgt) in 2005 to 68 million cgt in 2011.

The problem is even worse in China, with capacity set to increase by 525 percent over the same period from 4 million cgt to 25 million cgt.

Arthur Bowring, managing director of the Hong Kong Shipowners Association, said the industry has been hit by a massive "double whammy" of overcapacity combined with the most severe economic crisis in 70 years.

"We have had a rapid build-up of world trade over the past few years, which resulted in fantastic returns for those operating ships. Because of the massive amounts of cargo being moved, new ships were ordered which encouraged shipyards to increase capacity," he said.

"Then, of course, we had the economic crisis, which has led to a total drying up of export credit. The two things coming together has led us all into a bit of a mess."

0 Comments

0 Comments