|

|

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail Beijing Review, November 9, 2012

E-mail Beijing Review, November 9, 2012

During the past decade, China has become an engine of global economic growth, particularly after the global financial crisis.China's leading role in shifting global economic dynamics is an outstanding turnabout not seen since the Industrial Revolution, says Chen Ping, senior research fellow at the Center for New Political Economy at Fudan University and professor at the National School of Development at Peking University. Edited excerpts of his views follow:

The decade since China entered the WTO in 2001 has witnessed the development and growth of the China model. Many developing countries look to China as a model of growth in the context of fierce global competition.

The Western world underestimated China's capacity as a global player when it gained WTO membership. Few mainstream economists, Western or domestic, thought China would have a promising future as a WTO member. China would suffer from a collapse in its agricultural, financial and automobile industries, they insisted. Without tariff protection, they said, China's domestic enterprises could not challenge European and American multinationals as Japanese and South Korean enterprises had previously done.

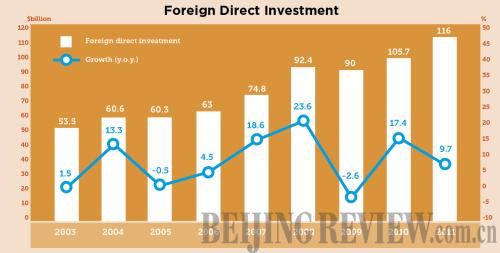

China has not only fully grasped the "rules of the game" but has gained the upper hand in the global arena. China's GDP has quadrupled to become the second largest economy in the world; its exports have grown five-fold; it is also the second largest recipient of FDI globally.

Since the global financial crisis in 2008, China's "big four" state-owned commercial banks have surpassed their American counterparts; China's auto output has surpassed the United States and Japan to top the world; its agriculture has undergone an unprecedented process of mechanization that freed much of its rural labor force to spur ongoing urbanization; enterprises like Lenovo, Huawei and Haier, have penetrated overseas markets by nurturing an array of quality brands.

Since joining the WTO, China has learned a lot from Western management approaches, as well as the so-called Western "rules of the game." For instance, China has actively responded to allegations of dumping in a variety of industries.

As China's achievements have been a focus of world attention for the past decade, frictions with other countries naturally occur. Trade is not just a process of exchanging goods—it can spark competition of productivity and scale. Losers have to face bankruptcy, unemployment and heavy financial burden. When defeated, they're always the first to complain about inequality before undergoing reform.

China's further growth must not only learn from the limitations of Western development—such as excessive consumption and environmental damage—it must also create new patterns in trade, one that features South-South cooperation in an effort to limit control that Western oligarchs have over natural resources and commodities markets. Only then can "trade wars" or "resource wars" be avoided in favor of sustainable economic development.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|