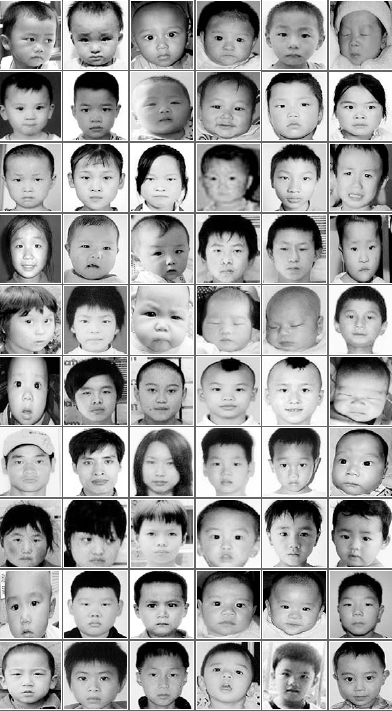

60 abducted children look for home

|

|

And despite the best police efforts, even if the children are found, reuniting them with parents whose names and whereabouts may be unknown can prove impossible.

So in a move to reconnect families, the Ministry of Public Security released information on about 60 rescued children on its website yesterday.

"It's the first time the ministry has published data about children whose parents couldn't be found through the national DNA database," lawyer Zhang Zhiwei, a volunteer with nongovernmental organization Baby Come Home, told China Daily yesterday.

The data includes the 60 children's photos, ages, the time they went missing and how to contact the department in charge.

"Even if I can't find my boy's photo on the website today, it's a blessing for desperate parents like us who have nearly lost hope," Tang Weihua, a mother who lost her 5-year-old son in 1999, told China Daily in a telephone interview yesterday.

About 30,000 to 60,000 children are reported missing every year, but it is hard to estimate how many are involved in trafficking cases, according to the Ministry of Public Security.

"The national DNA database has only 20,000 to 30,000 records, which is far from enough," Zhang said.

Information in the database is shared among the country's 236 DNA laboratories. It includes DNA of the missing children given by their parents, as well as samples taken from children suspected of having been abducted or from vagrant children with an unclear history.

Police have saved more than 2,000 missing children since a nationwide anti-trafficking campaign was launched on April 9, according to the ministry.

Zhang, who has inspired more than 20,000 volunteers to share information about missing children, said the building of the national database has been slow because of a lack of funds.

"The ministry has urged local police departments to fund this themselves, but the departments are complaining that the blood samples needed for DNA tests are too expensive," he said.

For example, one DNA test costs at least 2,400 yuan (US$350) in Beijing. The fee varies in different provinces, he said.

He also noted that a large number of missing children may be among the 100,000 or more children living in welfare institutions or orphanages.

Tang said the real criminals are those who buy children and "seek their happiness through the pain of other families".

"Many young moms have become volunteers and we are calling for more help in the campaign to fight traffickers," she said.

Zhang said most of the buyers treat the children well and most buy a child because they either want a son or because they are unable to have a child themselves.

As the children are generally young when they are kidnapped, they frequently develop emotional connections with the people who bought them, almost like they were real offspring.

"In some cases, families who get their children back even have to sign a contract with the buyers in order to comfort the children, who want to live with the buyers for several months every year," the lawyer told China Daily.

He said it is unreasonable that buyers can often avoid prison time if they cooperate with the police, which makes the price of their crime "too low".

0

0