Scholars bid gov't to abolish housing law

But what most often happens, experts said, is that local governments give construction clearance to estate developers or enterprises that pay off officials. It is then up to developers to negotiate with residents. If residents refuse to move, they will be forced out.

"Such twisted relations between urban development and personal property have resulted in many social conflicts," Shen told China Daily Tuesday.

The top legislature would not make any comments Tuesday.

However, South Metro News reported Tuesday that insiders with the legislature said the State Council Legislative Affairs Office and relative government departments are indeed researching possible changes.

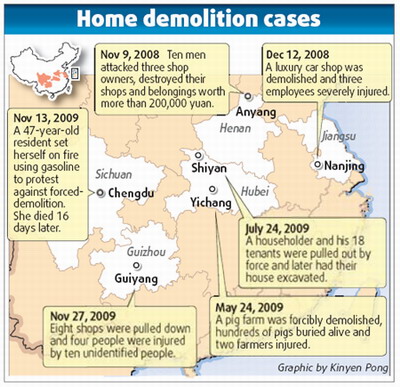

Shen said they felt it an obligation to push for changes after recent bloody incidents involving residents who were forced out from homes.

"It's time we rethink about the unfairness caused by, and price for urbanization and development, especially after the death of Tang Fuzhen," he said.

Tang shocked the nation by setting herself on fire to protest the demolition of her former husband's garment processing unit on Nov 13. She died of severe burning 16 days later at a local hospital, and the building was pulled down.

However, the local Chengdu government said Tang and her family were actually confronting law enforcement in a violent way. The government referred to the Housing Demolition and Relocation Management Regulation for seizing the garment building.

After Tang's death, many people angrily criticized the local authorities for the violent way in which the regulation was enforced.

"It's funny that those who conduct housing demolition support themselves with a regulation that disagrees with higher laws," said Jiang Ming'an, one of the five scholars.

0 Comments

0 Comments