From the height of success to the low of uncertainty

Martial arts students face the foe of doubt after graduation. Zhao Peiyu felt like he was on top of the world - and it was not because he was suspended almost 80 meters off the ground by steel wires.

|

|

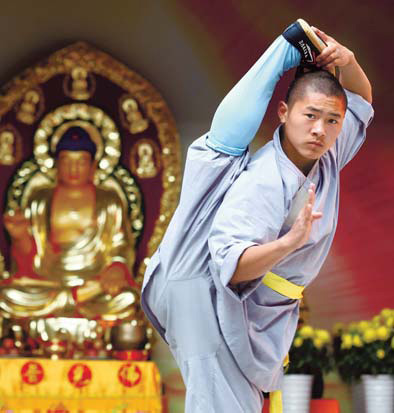

Chen Tao, a 15-year-old monk, practices martial arts at the Shaolin Temple in Dengfeng city, Henan province, in this file photo. |

On the night of Nov 12, the 19-year-old was among more than 1,600 kungfu students who performed at the opening ceremony of the Guangzhou Asian Games.

"We travel a lot to perform in different places but this time we represented the country's youth," he said proudly, pointing at the Asian Games logo on his T-shirt. "We strived to make it the most impressive show we could."

It is not the first time Zhao has taken center stage at a major event. His school, Tagou Wushu Sports Academy, also helped open the Beijing Olympics in 2008.

However, back home in Central China's Henan province, the teenager's mood was less upbeat. The fleeting excitement in Guangzhou had been unable to ease his growing fears about the future.

"I don't know where to go now I've graduated," said Zhao, who, after training in the Chinese martial art of wushu for more than seven years, feels he is only qualified to "be a coach or join the army".

Like thousands of others at secondary vocational schools in Dengfeng, one of the spiritual homes of wushu, Zhao's schooling in standard subjects like Chinese, mathematics and English has taken a back seat to improving his acrobatic and kungfu skills.

On a regular day, he gets up at 5 am to practice zuigun, a stick-fighting style, for roughly two hours before breakfast, usually a steamed bun and porridge. After half a day of classes, he returns to the training area until the late evening.

"Hours of training on the playground is a real test for juveniles," said Zhao.

At his age, most are talking about another type of test - the gaokao, the national college entrance exam that can potentially make or break a student's job prospects. Zhao is unlikely to ever sit the exam and has little idea about his options.

At least 90 percent of the students interviewed by China Daily this month at 10 wushu institutes admitted they do not know what they will do after graduation.

Zhang Xuemin, head coach at the city's Shaolin Temple Martial Arts Training School, said only three or four of its students continue their education at college every year.

In between performing at events home and abroad, most youngsters pin their hopes on earning jobs as coaches. Competition is fierce, however.

Shaolin Temple School has 260 teachers, mostly former students, and every year roughly 2,000 new graduates fight over just 50 vacancies on its staff.

If they fail to win spots at college or become coaches, the only other option is the army, said the school's deputy director, Men Zhendong. "The worst case scenario for graduates is to work as security guards," he added.

Men agreed that half a day of study is not enough to prepare youngsters for life after school, but then again many parents are unconcerned. He argued most children are sent to wushu schools to learn discipline, not book smarts.

"Most trainees at these schools were hard to handle at home," said director Zheng Hongqi, Men's boss. "Parents need an institute to take care of (the children), so they can dedicate their time and energies to making a living."

Coaches at Tagou Wushu Sports Academy, the biggest in China, also revealed that the vast majority of its 28,000 students were "problem youths" sent there to be "straightened out".

0

0