Land grabs threatening rural stability

Increasing instances of farmland being confiscated and of insufficient compensation being offered to farmers are harming the legitimate rights of country residents and posing a threat to social stability in agricultural areas, according to a new survey released by a top think tank.

|

|

Land grabs threatening rural stability |

About 37 percent of the 1,564 villages in 17 provinces and autonomous regions that were covered by the survey have experienced land confiscation since the late 1990s.

Farmers in 60 percent of the villages where land has been confiscated reported that they were unsatisfied with the compensation they received, according to the survey released by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences late last week.

The document was part of the academy's annual report on China's rule of law and was jointly conducted in mid-2010 by Landesa, a United States-based rural development institute, Michigan State University and the Beijing-based Renmin University of China.

The survey shows that the 1,564 villages that were studied only saw about 20 land confiscation cases in 2000, but that number had soared to about 180 in 2010, suggesting the problem was becoming more widespread.

The report did not make clear how many of the land confiscations were illegal, but said: "Illegal land confiscation has become the biggest threat to Chinese farmers' land rights and conflicts related to land have become a threat to the stability of China's rural society."

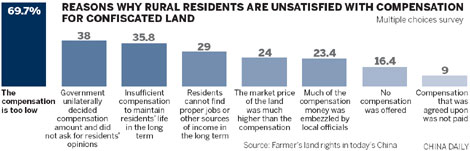

Among the farmers that were unsatisfied with the compensation they received after their land was seized, nearly 70 percent considered the amount was too low and 38 percent complained that they did not have a say in determining the amount of compensation they received.

The survey also found that 29 percent of the farmers who had their land forcibly taken from them did not receive any prior notice that is was about to happen.

Under current Chinese laws, rural land is collectively owned and farmers only have the right to use it but can not own it. The government has the right to confiscate that land if it is in the public interest.

However, as the survey suggests, in reality many cases of confiscation are not done for the public good but for commercial reasons.

In addition to confiscation, the illegal renting out of rural land has also been a problem, with motivated local governments sometimes helping ensure enterprises can rent farmers' land at a cheap price.

Under current laws, rural agricultural land is not supposed to be rented out for commercial uses in an attempt to protect farmland and assure the production of food.

However, illegal renting has been rising in recent years. In 2010, 39 percent of rural land was being rented to factories and companies, the report said. It noted that such practices pose a threat to China's food security.

In some cases, farmers were pressured to get off their land or even forced to vacate by local officials, who told them "the renting of the land was in compliance with an order from upper governments", the report said.

"My experience shows that in most villages, the village head is the decision maker about which land will be confiscated and which will be rented out and he or she is very likely to be the one who gets the most profit out of it," said Jiang Ming'an, a Peking University law professor who has paid close attention to the issues of land confiscation and forced home demolitions.

Jiang echoed the findings of the survey in suggesting that the current Land Administration Law should be revised to clarify "ownership of land".

"If it's owned by the collective community, then every farmer should have a say in whether land should be confiscated or sold," Jiang said.

The survey also suggests that the law should make a clearer definition of what is in the "public interest" to avoid illegal confiscation of land for commercial use. It also suggests raising the amount of compensation given to farmers.

0

0