Ageing Japan a warning to China

- By Geoffrey Murray

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, February 4, 2012

E-mail China.org.cn, February 4, 2012

A recent announcement by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) that the proportion of China's working-age population fell last year for the first time since 2002 probably went largely unnoticed. Yet, it is of major significance for the country's long-term economic health.

|

|

|

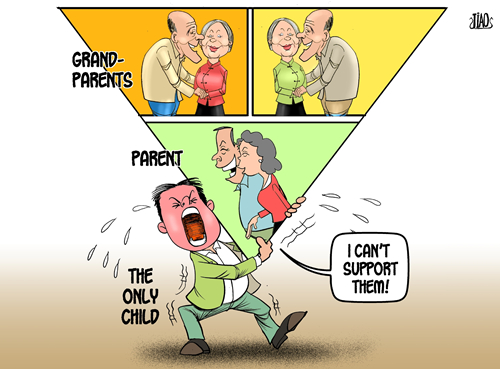

Inverted pyramid [By Jiao Haiyang/China.org.cn] |

The proportion of people in China aged 15 and 64 dropped 0.10 percentage points to 74.4 percent. This isn't a big change in terms of the country's huge population, but extremely important demographically when set against a low birth rate and a rapid increase in the number of senior citizens.

China's vast worker pool powered the explosive growth of its export-driven economy over the past decade, but, now, it faces a labor shortage as it seeks to move away from low-grade products into those with more added value. A lack of skilled workers is pushing up wages and adding to the burden of companies already facing shrinking global markets.

This is something that cannot be ignored, and, if an object lesson is needed, one only has to look at Asia's other economic giant, Japan.

While China is seeking to stabilize its population at around 1.6 billion by 2050, Japan is desperately trying to encourage more births to stop a trend that could result in its population shrinking by one-third by 2060. That shrinkage is going on now at a rate of a million people a year, but if the trend continues, by 2110, the population will fall from the present 127.7 million to around 42.9 million.

We're so used to talking of the global population accelerating out of control that it seems incredible to consider a major country being so reduced in what is a relatively short time span. Even more damaging for Japan, by 2060 almost 40 percent of the population will be aged 65 or over, further exacerbating the financial burden the country currently faces.

Japanese women simply aren't having babies and they have resisted every attempt by the government over the past 20 years to get them to change their mind. The national fertility rate was 1.39 in 2010, far below the replacement rate of 2.08 and the global average of about 2.5.

A weak economy discourages young couples from having children. Added to this is Japan's extremely high cost of living and extremely limited living space in urban areas, both which discourage large families.

In China, of course, the government's former "one-child" policy is a major factor in current demographic trends. Even so, there are a growing number of young urban couples who have deliberately chosen to join the "DINK" trend (double income, no kids).

Japan's success in extending life expectancy is also a major contributing factor to the country's lopsided demographic profile. In 2010, the figure was 86.39 for women and 79.4 for men; in 2060, these figures are expected to be 90.93 and 84.19 respectively - among the world's best, thanks perhaps to a fish-dominated diet.

Of course, a smaller population in itself is not a problem. Certain countries in Europe, for example, have far fewer people than Japan but enjoy great economic and diplomatic success on the global stage.

Japan currently needs fewer workers thanks to a long-time policy of shifting labor-intensive industries overseas and concentrating on highly automated manufacturing processes at home. China can do this, too, but at the risk of high unemployment and social instability.

What does matter is the top-heavy nature of Japan's population structure. The country's Health and Welfare Ministry says the number of people aged 14 and under will halve by 2060 to 7.91 million. By contrast the number of people aged 65 or older, which represented 23 percent of the population in 2010 will rise to 39.9 percent by 2060. This means a huge increase in social security spending, a burden the Tokyo government can ill afford as its public debt is already twice the size of the US$5 trillion national economy.

One way it is trying to cope is through a plan to double the country's sales tax to 10 percent by 2015. However, a drastic overhaul of pensions, employment and labor policy and the social security system is needed.

The Japanese may also have to face the prickly issue of immigration - bringing in more foreign labor to make up for local shortages - something they have always derided as a threat to the long-treasured homogeneity of society.

What does all this mean for China? There may not be population shrinkage, but there is certainly ageing. At present, there are about 130 million people aged 65 or older, and the projections are that this figure will grow to 300 million by 2030, imposing a huge financial burden on everyone.

For both China and Japan, the demographics pose a huge challenge requiring difficult and innovative decisions in terms of policies on social welfare funding, population control and employment and labor development. It's not going to be easy.

The author is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit: http://www.keyanhelp.cn/opinion/geoffreymurray.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.