A policy of open scientific data sharing benefits all

- By Richard de Grijs

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail China.org.cn, July 30, 2017

E-mail China.org.cn, July 30, 2017

|

|

|

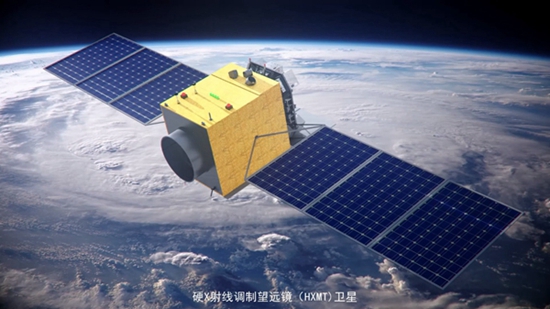

China’s first X-ray space telescope [File photo] |

The other day, reading a headline in the China Daily, “Data of China’s first X-ray space telescope to be open to global scientists,” I was both surprised and somewhat concerned.

Surprised, because it is international best practice in science to share data with anyone, no matter what their institutional affiliation, nationality or geographical location. I had therefore expected no less than an open and transparent data policy from the team running the Hard X-ray Modulation Telescope (HXMT), nicknamed Insight.

Concerned, because the headline implied that scientific policy makers apparently thought such openness was novel. It is not; open data sharing has been the international norm in the field of space science since the first scientific missions supported by NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA).

Of course, commercial and national security interests can preclude some open data-sharing, but an X-ray satellite designed to explore distant celestial objects to better understand their nature – including that of the massive “black holes” at the centers of many nearby galaxies – hardly pose a threat to national security.

This policy of openness – both in terms of data availability and data acquisition – has been enormously beneficial to both NASA and ESA. Their joint project, the Hubble Space Telescope, is arguably the most productive scientific instrument ever built.

Its productivity is due largely to the way it offers unrestricted access to anyone with a great idea – the competition is fierce, with “oversubscription rates” by factors of eight or more; however, if your idea is ground-breaking, it doesn’t matter where you are based.

The students and junior researchers in my team at Peking University routinely use Hubble observations that have languished in its Data Archive for years, perhaps never explored or used for other purposes.

The age of observational data in astrophysics doesn’t matter; the novelty of the results does – and by using years-old Hubble data, we have managed to publish a number of ground-breaking discoveries in prestigious journals like Nature.

Of course, we get the academic credit for those discoveries, but both space agencies also get what they hoped for: more publicity and a confirmation of their cutting-edge status.

Such are indeed the prospects for the X-ray observations the Insight module will obtain as well. No matter who publishes their scientific results, the eventual kudos go to the Chinese team responsible for the satellite’s development and operation.

By international norms, the scientists involved understand their data, as well as that obtained for any other scientist whose proposal is accepted, will be theirs for just a year, the ‘proprietary’ period.

For so-called “survey” facilities, like ESA’s current flagship mission Gaia (which will revolutionize studies and understanding of our own Milky Way galaxy), the timeline is somewhat different. Their data will still be made publicly available, but through annual data releases; the first Gaia release happened just recently.

So, my concern when reading the newspaper headline was that it might indicate an underlying reluctance by the scientific policymakers responsible for Chinese space missions to truly embrace a spirit of international openness. This would send a poor message about the scientific community on which I consider myself an integral and active member.

Fortunately, upon reading the full article, I was reassured that Chinese space scientists indeed want to contribute their novel achievements in high technology to the international community.

Perhaps it was just the headline writer who didn’t quite understand the potentially negative implication of his words. By joining forces with the greatest minds, scientific progress becomes ever more promising.

Richard de Grijs is a columnist with China.org.cn. For more information please visit:

http://www.keyanhelp.cn/opinion/RicharddeGrijs.htm

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China.org.cn.